Before a grandson of the “holy Yehudi,” a zaddik of the seventh generation, a merchant brought a complaint against another who had opened a business next to him and reduced his profits. “Why,” asked the zaddik, “do you attach yourself so to the business by which you nourish yourself? What really matters is to pray to Him who nourishes and preserves! But perhaps you do not know where He dwells; now then, it is written, ‘Love thy fellow as one like thyself, I am the Lord.’ Only love him, your fellow, and wish that he too may have what he needs, - there, in this love, you will find the Lord.” (Ref. 1: Buber, p. 230)

NOTE TO THE STUDENT: Because of the length of our commentary on this anecdote, we have divided this lecture into two parts. Part 2a briefly describes the hasidic context within which the anecdote arose, without which many beginning students would not understand the relationship of the merchant to the tzaddik. It also begins our commentary on the anecdote by discussing the idea of attachment. Part 2b of the lecture continues the commentary with a discussion of the concept of Shefa (Heb. “Overflowing” or “Abundance”) and a discussion of God’s dwelling place in the world.

Hasidic Context

Hasidism is the name of a revivalist movement founded in the mid-1700s by Yisroel ben Eliezer (1698 – 1760), better known as the Ba’al Shem Tov (“Master of the Good Name”), abbreviated as “BeSHT.” The word hasidism comes from the Hebrew hasiduth (“piety”), which is derived from the Hebrew root chesed (“lovingkindness”). Many of you will recognize that Chesed is also the fourth Sefirah in the sacred Etz Chayim (“Tree of Life”)

Hasidism came about in response to two main historical situations. First, the Khmelnytsky Uprising of the Cossacks and peasants of the Ukraine, Belarus and southeastern Poland and the Tatars of Crimea against the Commonwealth of Poland-Lithuania from 1648- 1654, coupled with political upheaval in Poland during the same period, was especially hard on the Jews in those areas. It is estimated that massacres and pogroms resulted in the deaths of 20,000 to 30,000 Jews (half the Jewish population) and the complete destruction of up to 300 villages and towns. The result of these events was the physical, political and economic destruction of Jewry in vast areas of southern and eastern Europe. Second, with the conversion to Islam of Sabbatai Sevi, the only person ever to be recognized by the whole of the Jewish world as the Messiah, the Jews fell into the grips of a deep spiritual depression. They were disappointed that their belief that the Messiah had come to liberate them from exile and oppression turned out to be a false hope. Secondly, Sabbatai Sevi’s apostasy was seen by most Jews to be a betrayal on the deepest level possible. Very few realized or accepted the mystical explanation offered by Nathan of Gaza and other kabbalists that the Messiah had come not for political and economic reasons but to do exactly what He did for spiritual reasons of tikkun.

The Ba’al Shem Tov sought to revive the spirit of Judaism within the Jewish people and did so by teaching that the way to God is not limited to the way of the urbane Rabbinic Torah scholar or to the oriental asceticism of the kabbalistic sages. Rather, according to his teaching each person, no matter how simple or uneducated, can have a direct and personal relationship (devekhut = “cleaving” or “communion”) with God within the fullness of ordinary life based entirely on one’s emotional responses to God’s Presence. That is to say that even an ignorant peasant can cleave to God through the pious experience of love, joy and ecstasy focused on binding oneself to God. In this way emotion and experience were elevated above study and intellect. He taught that God is everywhere and in all things (panentheism or acosmic monism) and, therefore, one can see the form of God and relate to God by hallowing everything in one’s everyday life. He taught that meditation and prayer with mystical intention (kavvanah) were vitally important aspects of hasiduth and could be pursued effectively by anyone.

Although Jewish rabbinic leaders in Lithuania (calling themselves the mitnagdim = “opposers”) led a vigorous opposition to the egalitarian hasidic movement, including the issuance of proclamations of excommunication against any who followed the BeSHT, they were unable to counteract the appeal of hasidism to the common people of rural south-eastern Europe. At its peak in the decades prior to World War I, hasidism claimed millions of members. The orthodox rabbis finally relented in their opposition in order to join forces against what they perceived as an even greater danger to Judaism, the Haskala, or Jewish Enlightenment.

Tzaddikism

One of the key elements of hasidism is Tzaddikism, the belief in a supreme spiritual authority, who mediates between the upper and lower worlds and serves as the final arbiter in disputes between members of the hasidic community. Each community had its own tzaddik (also known as a Rebbe), which it supported financially and to which it was loyal and obedient in matters of halakhah (Jewish Law). The first such tzaddik, of course, was the Ba’al Shem Tov. When the BeSHT died, Rabbi Dov Ber, the Mezricher Maggid (1704 - 1772) became his successor, and the movement was divided geographically into three areas in Eastern Europe, with tzaddikim named for each area. As the movement grew, more tzaddikim were named. It was tradition that each rebbe, prior to his death, named his successor, and commonly this was a son or grandson. Therefore, each branch or sect within Hasidism continued under the leadership of what amounted to a spiritual dynasty. For example, the BeSHT’s grandson eventually became the leader of BeSHT’s sect, and his great grandson, Rebbe Nachman, became the founder of his own Hasidic sect. Many of these dynasties, e.g., the Lubavitcher-Chabad, Ger, and Brezlov, to name a few, are still in existence.

Martin Buber, an existentialist philosopher greatly influenced by Kierkegaard, converted to hasidism later in his life and became one of the greatest exponents of the movement and its belief system. In his 1943 essay titled “Love of God and Love of Neighbor” (Buber, pp. 215-248), Buber refers to various tzaddikim in relation to the “generation” of descent from the founder of hasidism, the Ba’al Shem Tov. It is in this spiritual, religious and social milieu that the events of the anecdote occur. .

We shall now discuss the anecdote and its teachings.

Commentary on the Anecdote

Before a grandson of the “holy Yehudi,” a zaddik of the seventh generation, a merchant brought a complaint against another who had opened a business next to him and reduced his profits.

We have here something that has happened in business since the beginning of trade itself. An established merchant is dismayed to see his former monopoly of the local market challenged by a competitor who has opened up shop right next door. The first merchant has had to reduce prices to compete with the newcomer, and this has reduced his profits. Who wouldn’t be upset? Within the context of the hasidic community, his remedy is to lay his complaint before the local rebbe (tzaddik), who has the unquestioned authority to interpret Jewish Law and decide how to resolve the conflict.

This particular rebbe is a tzaddik of the seventh generation (i.e., seven generations removed from the Ba’al Shem Tov), and, moreover, is the grandson of Jaacob Yitzhak, a famous fourth generation tzaddik so highly respected that he is known simply as the “holy Yehudi.” This detail is important because a tzaddik derived his stature not only from his own merit but in many cases even more so from the yicchus (Yiddish, “status”) of his forebears.

Attachment

“Why,” asked the zaddik, “do you attach yourself so to the business by which you nourish yourself?

How many of us are totally wrapped up in our businesses or jobs, taking them home with us, losing sleep over them at night, giving up evenings and weekends with our spouses and kids? Consider this teaching from classic compilation of hasidic sayings:

“Man is primarily his mind. . . . One should therefore keep in mind this thought: ‘Why should I use my mind to think about physical things? When I do this I lower my mind by binding it to a lower level. It would be better for me to elevate my mind to the highest level, by binding my thoughts to the Infinite.’ . . . Even physical things must serve the Creator in a spiritual manner. It is thus taught, ‘They are My slaves, and not slaves of slaves.’” (Ref. 2: Imrey Tzadikim, p. 18c).

We are our thoughts. I’ll say that again – We are our thoughts. We become that which we desire and dwell on most often. God has given us the power of choice, and we exercise that power constantly. The greatest of our choices is between the Yetzer ha-Ra (the evil urge) and the Yetzer ha-Tov (the good urge). Rarely do these two urges present themselves to us as clear-cut black and white opposites. More often they are subsumed in more ambiguous choices, such as who we think we are and what kind of person we want to be. These issues cut to the quick of our identity.

Are we the loving, supportive husband and devoted, caring father who is always there for his wife and children? Or are we the totally driven mid-level manager, fighting his way upstream to that next rung on the corporate ladder – the one that will reward his hard work and sacrifice with greater status, power and money? “Both,” you might be tempted to reply, neatly “solving” the dilemma by pretending to have a unique ability to wear both hats. But this is not truly possible, for just as a man cannot wear two hats at once but has to choose which hat to put on, the same is true of one’s identity. One cannot have one set of ethics while he is at work engaging in cut-throat office politics and implementing corporate mandated “take no prisoners” business policies and practices and another when he comes home or goes to church. Sooner or later you will be forced to choose one or the other identity as each competes with the other for possession of your ego, your sense of “I,” of whom you are.

Possession by the Persona

On this subject, C. G. Jung says:

“Possession can be formulated as identity of the ego-personality with a complex. A common instance of this is identity with the persona, which is the individual’s system of adaptation to, or the manner he assumes in dealing with, the world. Every calling or profession, for example, has its own characteristic persona. It is easy to study these things nowadays, when the photographs of public personalities so frequently appear in the press. A certain kind of behaviour is forced on them by the world, and professional people endeavour to come up to these expectations. Only, the danger is that they become identical with their personas – the professor with his text-book, the tenor with his voice. Then the damage is done: henceforth he lives exclusively against the background of his own biography. . . . One could say, with a little exaggeration, that the persona is that which in reality one is not, but which oneself as well as others think one is. In any event, the temptation to be what one seems to be is great, because the persona is usually rewarded in cash.” (Ref. 3: Jung, pars. 220 –221)

So essentially, the persona is the mask and costume we put on before going out the door. It is the impression of ourselves that we want others to believe we truly are. So to the neighbors, we are “that quiet guy next door, who keeps his yard and house up quite nicely, but about whom they know very little else. To our boss, we may be the employee who always gets his reports in on time even if he has to stay late every night during the last week of every month. The danger, as Jung says, is that we may begin to identify with our persona, i.e., come to believe that we are the public mask, meaning that we have forgotten who we really are inside. When this happens our sense of values and priorities likewise becomes confused, and relatively unimportant things can take on the aura of extreme importance.

For example, if we have identified with the persona of the “successful career man or woman,” we begin to think that we must portray that image to our neighbors and friends. A successful man has the physical things to show for his success – a nice, big, new house, at least two cars and, perhaps even an SUV or pickup truck, a vacation home on the lake, a boat for the lake, motorcycles or ATV’s, a Winnebago, membership in an exclusive golf club, and the list goes on. That’s the point – the list always goes on. No matter what one has acquired, it is never enough. There is always one more thing that you need to get, and then it will be enough. How many times have we seen that eventually a man begins to think, “My wife is getting old and dumpy. She doesn’t fit in anymore. In fact, she’s holding me back in my career.” So he divorces the first wife and goes out and gets a “trophy wife.”

Slaves of Slaves

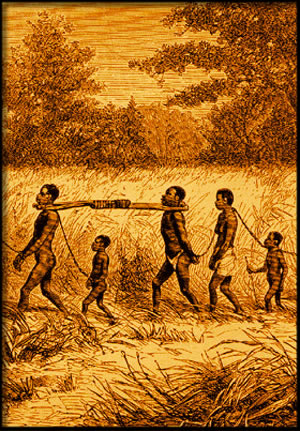

Sadly, this kind of insane behavior is all too commonplace. One cannot find lasting satisfaction in the physical world – in money, sex, or power. It just isn’t there. The only place one can find satisfaction is in the spiritual – in a relationship of love for and fear of God. When we fail to realize this fundamental truth, we become, as Carl Jung put it, “possessed” by the archetype of our persona. We no longer are our own person, but a slave to an image that we are projecting to fool others into believing we are something we are not. Pretty soon we no longer feel in control of our own life. We feel cheated because we see that life is fleeing from us with the passing of each day, and yet all we do is work every day and night to pay for “things” that have no real meaning for us. Somehow, we must awaken from the evil spell under which we labor our lives away and ask ourselves who’s in charge here. Do we own those things or do they own us? Or as the teaching above concluded, we must take charge and say: “They [my possessions] are My slaves, and not slaves of slaves.” (Imrey Tzadikim, p. 18c). We must cast off the yoke of slavery to the things of the physical world. Before we can free others we must free ourselves.

Sri Ramakrishna, the 19th century Indian Avatar, upon whose teaching Vedanta Hinduism is based, said:

“Pray to God that your attachment to such transitory things as wealth, name, and creature comforts may become less and less every day.”

It is from this perspective that the tzaddik asked the merchant:

“Why,” asked the zaddik, “do you attach yourself so to the business by which you nourish yourself? What really matters is to pray to Him who nourishes and preserves!”

We will continue our discussion of this teaching in the next installment of this lecture.

Baruch HaShem.

Reb Yahoshua Nesher ben Yakov Leib (YaNYaL)

___________________________________

Notes and References

Image: untitled, http://www.antislavery.org/breakingthesilence/upfromslavery.shtml

Ref. 1: Martin Buber, Hasidism and Modern Man, Edited and Translated by Maurice Friedman, (Humanity Books: New York, 1988)

Ref. 2: Imrey Tzadikim, p. 18c, cited by Aryeh Kaplan, Meditation and Kabbalah, (Red Wheel/Weiser, LLC, York Beach, ME, 1982)

Ref. 3: Carl G. Jung, The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious, Collected Works, Vol. 9, Part 1, (Princeton University Press: Princeton, New Jersey, 1969)

The Kabbalah of Reb YaNYaL

Today's Teaching

The Mitzvot of Love, Part 2a: "The Yoke of Attachment"

Torah Verses for Today’s Lesson: Deut. 6:5, Lev. 19:18